Jackie Pearson continues to examine what it is like to live without an elected local government, this time looking at the report of Commissioner McCulloch who conducted the public inquiry into the “financial crisis” which resulted in Central Coast Councillors being suspended and then sacked.

McCulloch’s public inquiry report stuck to the narrow terms of reference set by the Local Government Minister and concluded that the elected councillors were ultimately responsible for the financial crunch that occurred in 2020, whereas the highly-paid operational executives and experts, who the councillors relied on for guidance, were deemed to be “somewhat unhelpful”.

Slight rewrite

The report contained statements that were a revision of the events that resulted in the merger of Gosford City and Wyong Shire Councils in 2016.

McCulloch stated, for example, that Gosford and Wyong Councils voted in favour of merging and did so voluntarily.

In fact, only one of the two councils was in favour of the merger and to suggest otherwise shows a lack of local knowledge and context. The other was forced to yield on the basis of promises of funding for the new entity or a lack of funding if they declined to merge.

Gosford councillors only agreed to merge kicking and screaming, labelling it a “shotgun wedding”. The idea councillors enthusiastically and voluntarily agreed to the merger across the two councils is not correct.

Fit or unfit?

It is ironic that the McCulloch report compared the situation facing Central Coast Council to the measures used by TCorp in 2012-13 to determine which councils needed to be merged and which were sustainable.

The Commissioner’s report concluded that within four years of its creation, the much-lauded Central Coast mega-council, brainchild of former Premier Baird and former Local Government Minister Toole, was financially unsustainable.

The same conclusions had been drawn about the financial sustainability of both the Gosford City and Wyong Shire Councils in 2015-16 – they were declared financially unsustainable, “unfit” for the future. Both sets of residents and rate payers were told at the time that the new, merged council would be financially robust and “fit” for the future.

According to Commissioner McCulloch’s report, Central Coast Council was, by October 2020, as unsustainable and in substantially more debt that either of its forerunners.

“Somewhat unhelpful”

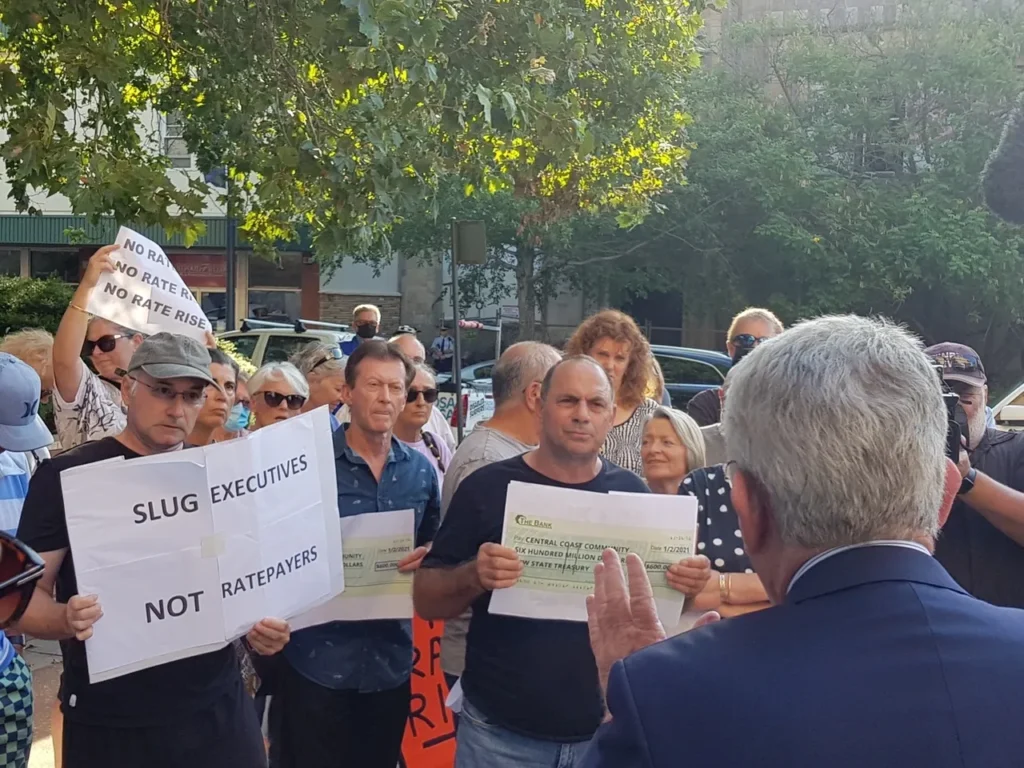

McCulloch found that Central Coast Council’s response to the financial problems it was facing by 2020 was too little and far too late. She concluded that “Ultimately the responsibility for the fate of the Council rests with the councillors”.

However, a great deal of the detail in the McCulloch report outlined how the ‘operational’ arm of the council, the professional executives appointed to deliver the council’s programs and services, had failed to fulfill their responsibilities.

The General Manager, CFO and several members of the executive leadership team left their jobs following the 2020 meltdown or have quietly moved on since, but none has been sacked and there was very little in the McCulloch report about changes needed to stop future operational catastrophes such as mismanagement of restricted funds.

McCulloch said, for instance, that the elected councillors “were not adequately supported by a General Manager who was able to provide strong leadership of the staff on financial matters at the time it was needed”.

The General Manager’s contract was paid out. He subsequently took defamation action against Interim Administrator Dick Persson which was discontinued.

The Commissioner conceded that prolonged periods without a permanent General Manager and Chief Financial Officer had a part to play in the cashflow crisis of October 2020.

The appointment of a CFO in May 2019 who had “no experience in local government or running a business” is also mentioned.

In May 2019 an IPART determination on the council’s water pricing took $39 million dollars out of the council’s hands over three years. This occurred while COVID-19 was having substantial impacts on revenue and services.

McCulloch said that, instead of reducing capital expenditure, the Council allowed the budget deficit to increase. Again, whilst laying the blame for this situation at the feet of the elected councillors, which subsequently resulted in their sacking, the McCulloch report clearly outlined the failings of the operational arm.

For instance, according to the public inquiry report, on 27 May 2019 the council resolved to approve water, sewerage and stormwater drainage fees and charges for 2019-20 consistent with the IPART determination.

However, according to McCulloch, “The report on the item did not mention the large difference between the revenue from water, sewerage and stormwater drainage fees and charges projected by Council’s submission to IPART and the revenue available under the IPART determination.”

It was not until 3 June 2019, after the councillors had voted on the water and sewer fees, that they were given a staff presentation regarding the IPART determination.

“The briefing paper explained that the operating result before capital grants and contributions would move from the publicly exhibited deficit of $7.7 million to a projected deficit of $18.6 million”.

Furthermore, the briefing document “did not make any recommendations for budget adjustments other than to include additional expenditure on water and sewer capital works of $1.4 million as required by the IPART determination.

“It somewhat unhelpfully stated in its conclusion: Councillors must feel appropriately informed and comfortable before signing off financial reports or agreeing to financial commitments. Councillors need to advise specifically what additional information they require in order to be appropriately informed and comfortable.”

These comments have been disputed by several former councillors. One told The Point, “I don’t understand how the Commissioner could make that statement when the presentation to councillors on 3 June 2019 states that staff did make adjustments…and this presentation was forwarded to the Commissioner during the Public Inquiry so I don’t believe that it is true to say that ‘no adjustments were made’.”

The Point understands those adjustments included changes to the Mardi to Warnervale pipeline project, a reduction in the stormwater drainage budget, reduced service levels for some maintenance work, deferral of some drainage and detention basin projects and deferral of $11.9 million of capital works projects.

According to Commissioner McCulloch, “there is no documentary evidence” of budget changes.

According to McCulloch, the CFO “left it to his staff to make decisions about how to adjust the budget in the light of the IPART determination …The CFO did not direct or lead the councillors in any meaningful way and at least some of the councillors behaved recklessly in the management of Central Coast Council’s finances. Central Coast Council suffered from a lack of financial direction from the time of Mr Naven’s (former CFO) departure in August 2017 until the time of the appointment of Ms Cowley in July 2020.”

Seeing red

Roslyn McCulloch’s report also addressed the spending of restricted funds without the knowledge or permission of the elected councillors or Local Government Minister.

The Commissioner reported that the CFO (appointed in 2019) “admitted that he ought to have known that unrestricted funds had fallen into the negative, that he did not know who else in Central Coast Council might have known about that fact, that he was aware that, due to COVID-19, cash could be an issue”.

The Commissioner found that the inexperienced and under-qualified CFO “may have facilitated the lack of information flowing to councillors about the situation and lack of action to counteract the downward trend of Central Coast Council’s cash position.”

McCulloch also reported that in 2019 when PWC was called in to take a look at council’s finances, it found “certain limitations to developing rigorous council budgets including a lack of available underlying data, a lack of consistent understanding and approach to financial planning, a lack of asset management planning beyond a 12-month horizon and a lack of clear links between the strategic and operational outcomes tied to finances”.

One of the substantial mysteries of the whole financial saga that Commissioner McCulloch did not solve was how the October 2019 investment report was changed, perhaps to cover up the fact that the balance of unrestricted cash held by Council had fallen below zero.

“Mr Norman was not aware of the change to the format for the October 2019 Investment Report nor was he aware that the balance of unrestricted cash had slipped into the negative. In fact, he was not aware of the continued deterioration of the unrestricted cash position until after he left Central Coast Council on 24 April 2020.

“He did accept that the October 2019 Investment Report was signed off by him,” the McColloch report said.

Commissioner McCulloch also noted that the financial information provided to councillors was not easy to read and was sadly lacking in attention to trends.

Her report carefully documented the decline in the budgetary position from 2019 and throughout 2020.

While concluding that the councillors were ultimately responsible for the financial crunch that came in October, the McCulloch report included many examples of failures on behalf of the operational arm of council.

For example, according to the Commissioner’s report: “The draft budget (for 2020-21) came before Council on 23 March 2020… The report which accompanied the draft budget disclosed that it proposed an operating deficit (before capital grants and depreciation) of $32.5M. The 2019-20 Long Term Financial Plan had forecast a deficit of $16M. The report stated that the difference arose from a decrease in development application fees, reduction in interest income, increase in emergency services levy, increase in Holiday Park management contract costs, increase in costs of the development of Coastal Management Plans and integrated water cycle strategy and costs to implement LED streetlighting. No figures were provided to indicate the individual reduction in income or increase in expenditure relative to those items.”

While it is true that the information about the decline in Central Coast Council’s finances and the use of restricted funds “was there if one knew where and how to look”, the bulk of evidence McCulloch received during the public inquiry indicated that councillors were not being properly informed by the operational arm of the council.

The investment reports from October 2019 until the financial crisis, were designed to obfuscate rather than elucidate.

The staff of Central Coast Council responsible for those reports bear a significant responsibility for the lack of knowledge on the part of the councillors for the use of restricted funds and, hence for the loss of the elected council, sale of community assets and price hikes that the community continues to bear.

What can you do?

If you live on the Central Coast and you do not believe the public inquiry has resolved the issues at Central Coast Council, contact your local state MP and encourage them to work with their parliamentary colleagues to call for a Legislative Council (upper house) inquiry into Central Coast Council before the March 2023 state election is held.

If you live in another part of the state that has also been subject to a forced council amalgamation, subsequent rate hikes or your council is also under administration, contact your local state MP and encourage them to work with their parliamentary colleagues to have a Legislative Council inquiry into the failed Fit for the Future 2016 council mergers program.

Residents and rate payers must be able to expect the state parliament to fully examine what has gone wrong with local government across NSW since 2016. In particular residents and ratepayers in merged councils which have failed financially or are weaker than the previous councils deserve an explanation and ongoing state government financial support to fix the failed mergers.