If climate change doesn’t end up devouring the Central Coast, the interest on commercial loans negotiated at the end of 2020 may drown the region’s debt-riven Council, Jackie Pearson reports in part three of this series on the Coast’s local government (or lack thereof).

“If you torture numbers long enough, they will tell you anything,” the old saying goes and there is a strong element of that in local government financial reporting on the Central Coast since at least the early 2000s. In March 2016, weeks before its forced amalgamation with Wyong Council, Gosford City Council’s CEO declared that its total loss from dodgy Collateralised Debt Obligations (CDOs) in the Global Financial Crisis totalled $19.6 million.

At around that time, according to the report of Roslyn McCulloch, who was the Commissioner for the Public Inquiry into Central Coast Council’s 2020 financial meltdown, Gosford City Council had $155 million in outstanding loans and Wyong Shire Council had $178 million in loans outstanding.

Both were deemed to have a healthy debt service cover ratio (DSCR) of 3:1 against a benchmark of greater than 2:1 and it was concluded that the loans could be adequately serviced.

Just a few years later, at the end of 2020 Rik Hart, in the role of interim general manager of the Central Coast Council (under administration), has said (repeatedly) that he was scrambling to find commercial lenders willing to bail out the council to the tune of an additional $150 million and Interim Administrator Dick Persson was telling anyone who would listen that the Council was in debt to the tune of over $500 million.

There is no disputing that 2020 was a tough year financially for the Central Coast Council but there was also a fair bit of number torturing going on.

Questions that have not been answered by the McCulloch Inquiry that the community would like answered before the next NSW state or local election include:

1. Why, in the last months of 2020 didn’t then NSW Local Government Minister deliver the support she promised to the Council to see it through its short-term cash crisis?

2. Why did Hart and Persson get away with implying that the whole $500 million + debt had been accumulated between 2016 and 2020 when, clearly, the combined debt of the new Council at its very creation was $333 million?

3. Why didn’t the operational arm of the council inform the elected arm that it had run out of cash and was spending restricted reserves?

4. Why wasn’t Central Coast Council allowed to borrow the $150 million required to repair the cash crisis from T-Corp, instead forced to negotiate deals with commercial borrowers via new CFO Natalia Cowley’s industry contacts?

There are many other questions that haven’t been answered satisfactorily by the public inquiry but that’ll do for starters.

Subtle little accounting change

The McCulloch report does explain one very important element of the restricted reserves saga that was one very substantial cause of the October 2020 cash crunch. Until 2016 the consolidated financial statements of the two former councils had accounted for the funds collected for water supply and

sewerage services as externally restricted funds. That meant those funds could not be spent for purposes other than water and sewer without the permission of the Local Government Minister.

However, in the consolidated financial statements of Wyong Shire Council and Gosford City Council for the period 1 July 2015 to May 2016 that practice changed. Please note this took place after the sacking of those councils and the formation of Central Coast Council during the first period of administration under Ian Reynolds.

The financial reports for 1 July 2015 to 12 May 2016 for the former councils had the following notes

6(c), 7 and 10(a) which cross-referenced a change in accounting policy.

According to McCulloch, “No reference was made to it in the overview, the section entitled ‘Understanding Council’s financial statements’, the Statement by Management signed by the Administrator, the GM and the CFO, or the independent auditor’s reports.

“Mr Dennis Banicevic, then of Price Waterhouse Coopers (PWC), … addressed the Council meeting on 21 December 2016. He did not refer to the change in accounting policy directly, but he did offer a caution in relation to the apparent level of working capital. Page 9 of the consolidated financial report indicated that total cash, cash equivalents and investments had improved from $156 million to $158 million.

“Mr Banicevic said that once the restricted components were stripped out, the actual working capital was a more modest $48 million and that would be the basis for the new Council to develop any budgets going forward.”

It is not clear from the public inquiry whether or not those managing the books at Central Coast Council from 2017 to 2020 understood the significance of this accounting change.

According to the current CFO, Natalia Cowley, staff continued to handle water and sewer funds as restricted funds but that doesn’t really explain why some of those funds were spent without permission of the Minister or knowledge of the Councillors.

The final report from Administrator Reynolds may have given the elected Councillors a false sense of security about the financial standing of the Council they ingherited.

“Council’s finances are sound and strong and the fully funded Operational Plan for 2017-18 is already rolling out,” Reynolds said.

The case of the missing number

From January 2017 the Council’s investment report included a table which showed source of fundsand Values in $’000s for the investment portfolio, transactional accounts and cash in hand; it also showed the total of Restricted Funds and Unrestricted Funds

The McCulloch report said the table was usually located in a part of the report headed “Council’s Portfolio by Source of Funds”. The unrestricted funds represented the operating capital available to Council at any given time.

The investment report for October 2019 no longer included a row within the table describing the value of unrestricted funds.

“The likely reason for its omission was that in October 2019 unrestricted funds fell into the negative,” McCulloch concluded. That occurred a whole 12 months before Councillors were suspended following revelations that the Council had been spending restricted funds.

“The investment report for October 2019 did not contain any additional comment to alert the reader to the fact that unrestricted cash was in the negative. Unrestricted cash remained negative until the Council was suspended in September 2020.

“At no time was any notation made in an investment report to alert the councillors to that fact.”

“The Councillors were never informed that the unrestricted funds had been exhausted nor were they warned about the consequences of having no unrestricted funds available.”

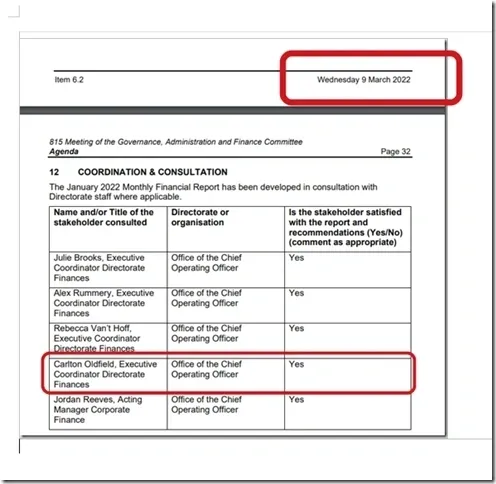

Where’s Carlton?

“The author of the Investment Report for October 2019 was Mr Carlton Oldfield, Unit Manager, Financial Services. The executive responsible for that report was Mr Norman, the CFO,” Commissioner McCulloch said in her report.

“Mr Norman was not aware of the change to the format for the October 2019 Investment Report nor was he aware that the balance of unrestricted cash had slipped into the negative. In fact, he was not aware of the continued deterioration of the unrestricted cash position until after he left CCC on 24 April 2020.

“Mr Norman could not explain why Mr Oldfield did not tell him that the unrestricted cash position had fallen into the negative, believing that Mr Oldfield had taken sick leave at that time.

“Council records show that Mr Oldfield did not take extended sick leave until late August 2020, well after Mr Norman’s departure.

“Mr Oldfield was appointed as the acting CFO when Mr Norman left on 24 April 2020, however he relinquished that role and returned to his position as Unit Manager, Financial Services on 11 August 2020.

“Regrettably, this Inquiry did not have the benefit of hearing from Mr Oldfield as he was not able to be located.”

It is quite alarming that an Inquiry directed by the NSW Office of Local Government did not have the resources to track down Mr Oldfield who was employed by the Gold Coast Council in Queensland from around June 2021, months before the Central Coast Council Public Inquiry, and appears still to be employed by the Gold Coast Council in the role of Executive Coordinator Directorate Finances.

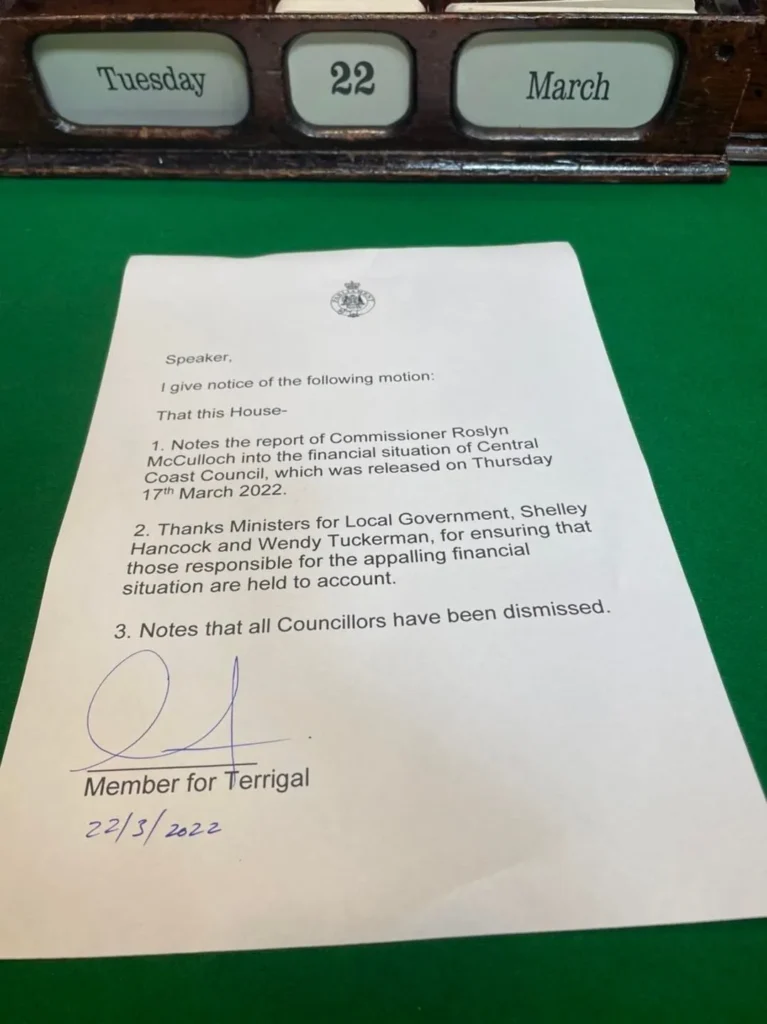

This is one clear reason why a Legislative Council Inquiry into, not only the Central Coast Council but the failed amalgamations of multiple councils across the state, must be held before the next NSW state election which is due in March 2023.

Such an inquiry would be able to compel a witness, such as Mr Oldfield, to give evidence. However, it must be said that the McCulloch Inquiry could have tried a little harder to find Carlton!

The Councillors were the last to know

“The investment reports from October 2019 until the financial crisis, were designed to obfuscate rather than elucidate” is an understatement. The staff of Central Coast Council responsible for those reports bear a significant responsibility for the lack of knowledge on the part of the Councillors for the use of restricted funds.

By May 2020 the Councillors were facing a deficit of $41.6 million but they did not realise the bottom line was much worse than that because there was money missing from restricted funds. According to Dick Persson, before the Council was placed under administration for a second time in October 2020, staff had spent all available internally restricted funds and were munching their way through externally restricted funds.

The NSW Audit Office, which took over as auditor of all NSW councils in 2018, did not raise any significant matters according to McCulloch.

However, an earlier interim management letter sent to Council staff from the Audit Office “raised issues of moderate risk relating to: risk management culture; legislative compliance; controls over manual journals, adjustments to customer accounts, procurement governance, changes to vendor master files, changes to payroll master files. In other words, the NSW Audit Office was questioning financial practices within the operational arm of the Council well before the financial crunch. The public is left to trust those matters have been addressed.

In August 2020 the Audit Office published a performance audit report entitled “Governance and Internal Controls Over Local Infrastructure Contributions”. The audit assessed the effectiveness of governance and internal controls over local infrastructure contributions (LICs) including at the Central Coast Council.

According to the report between 2016 and 2019 the LIC balance doubled from $90M to $196M.

During that period the LIC contributions (including works in kind and land) averaged $33M per year against average expenditure of $7M per year. The report noted that an increasing balance with relatively low expenditure represented infrastructure that developers had paid for but which the community had not received.

The report also noted that the Council needed to adjust its 2018-19 accounts by $13.2M to repay the LIC fund for administration expenses “unlawfully claimed” under 40 contributions plans since 2001. In other words, the Audit Office uncovered that some restricted funds had been used by the operational arm of the Council dating back to 2001.

However, given the balances recorded in that report it appears that a great deal of money was taken out of restricted funds, without the knowledge of Councillors, during 2019-20.

What of that massive debt?

Interviews conducted with Councillors by The Point shortly after their initial suspension in 2020 indicated that they believed they were the last to know about the use of internally and externally restricted funds.

It is a point of law whether or not that accounting practice change made during the first administration period means the use of restricted funds was or was not “unlawful”. The NSW Solicitor General advised that the accounting change meant the use of restricted funds from water and sewer may not have been unlawful.

Rik Hart who, by the time of that Solicitor General ruling, had moved from the role of Acting CEO to Administrator, got legal advice to contradict that of the state’s Solicitor General and said the Council would revert to treating water and sewer funds as restricted. By doing so he justified the decisions he made as General Manager to turn to commercial banks to borrow $150 million on terms undisclosed to the public, to “pay back” the restricted funds and right the ship.

As a consequence of those commercial borrowings, Mr Hart has also overseen an extensive asset sale program (again without very much public access to information) and been given on IPART special rate variation, with potentially more to follow. IPART will soon also decide on an adjustment to water and sewer pricing which will also be substantial including inflation adjustments.

What were the terms Mr Hart and Ms Cowley agreed to when they turned to “borrowers of last resort” – total interest cost, trail commissions and other costs to be born by the rate payers and residents for many years to come? Due to “commercial in confidence” the public may never know.

Have the practices and obvious lack of controls that resulted in the use of restricted funds been addressed by the new CEO, David Farmer?

Mr Farmer has been delegated authority to conduct some massive and controversial projects including potential development of the Gosford waterfront and restructure, including sale, of Council’s water assets. These matters are being pushed forward with little transparency and without the oversight or input of Councillors.

Meanwhile, public assets are sold and the prices charged for services, land and water rates escalate in order to pay back a commercial debt that could have been avoided had Central Coast Council been able to borrow from TCorp or even been allowed to gradually pay back used internally and externally restricted funds as “internal loans”.

What you can do

1. If you are a Central Coast resident or ratepayer, educate yourself about how your local council is operating. Watch meetings on zoom or attend in person, register to speak at the forum held before each monthly meeting. If you have concerns write to [email protected]

2. Council matters are state government matters so contact your local MP and ask that they push for a Legislative Council inquiry into the Central Coast Council and the whole 2016 amalgamation process across the state before the next election.

3. If you live on the Central Coast or in any of the other amalgamated Councils in NSW, contact the NSW Local Government Minister now Wendy Tuckerman and Shadow Minister Greg Warren and tell them we need a Legislative Council inquiry into the failed amalgamations before the next state election

4. Here’s a list of the councils amalgamated in 2016: Armidale Regional Council; Bayside Council; Canterbury-Bankstown; Central Coast; City of Parramatta; Cootamundra-Gundagai; Cumberland; Dubbo; Edward River; Federation; Georges River; Hilltops; Inner West; Mid Coast; Murray River; Murrumbidgee; Northern Beaches; Queanbeyan Palerang; Snowy Monaro; Snowy Valleys