Over 50% of coastal wetlands in NSW have been destroyed since colonisation and the NSW Government is ill-equipped to take advantage of the emerging Blue Carbon market to help protect and restore these ecosystems.

By Jacquelene Pearson

In this four-part special report, we will explore the health of wetlands in NSW, starting with an overview of the state’s coastal wetlands and then focusing on three NSW Central Coast case studies.

Let’s first look at the present health of the state’s coastal wetlands. Acid sulphate soils, pollution and pesticides, over-development and sea level rise all place coastal wetlands in peril.

Sam Johnson, Coastal Wetlands Community Organiser for the NSW Nature Conservation Council (NCC), has visited coastal wetlands up and down the eastern seaboard in the past 12 months where he has witnessed wetland devastation through to successful restoration.

Visit The Point YouTube channel to watch the whole video with Sam Johnson!

“We know for sure that well over half of coastal wetlands have been lost in NSW since colonisation began,” Johnson told The Point.

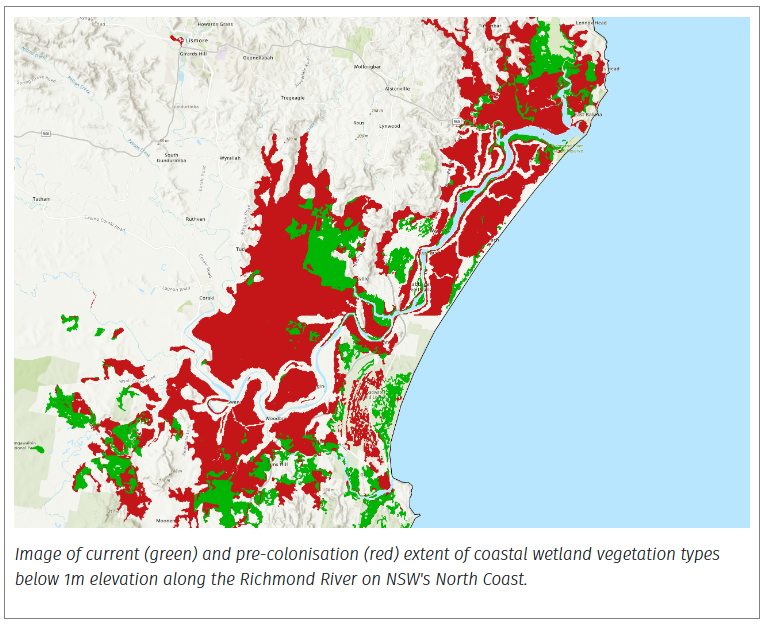

“We have looked … at the vegetation models pre-clearing, so pre-colonisation to now, and we have specifically focused on low-lying wetlands (1m elevation or lower) and that is where you have seen some significant losses,” he said.

| Catchment | % loss of coastal wetland since colonisation |

| Tweed River | >89 |

| Richmond River | 75 |

| Sydney | 84 |

| Central Coast | 65 |

NCC has published an interactive map so coastal residents can look at the percentage of coastal wetlands lost in their local area.

The rates of loss differ between catchments and habitat types, according to Johnson.

Saltmarsh endangered

“One that we are particularly concerned about is saltmarsh which in most of NSW is now an Endangered Ecological Community (EEC) at risk of sea level rise more than other systems,” he said.

Saltmarsh is important for migratory birds: “They really like that roosting and feeding habitat where they have a good line of sight of potential predators. It is effectively the best habitat that a migratory bird can get, and they are increasingly threatened with extinction.

“The reason we are worried about saltmarsh going into the future is because they have probably the lowest adaptive capacity to sea level rise in that they get easily inundated.

“Going into the future we need as much as we can to have these ecosystems survive.”

Why wetlands matter

The NCC defines wetlands as any ecosystem that is permanently or regularly inundated with water – freshwater, salt water or somewhere in between. They are clearly important habitats for countless threatened species particularly migratory birds, bats, fish and plants.

“Our campaign considers everything from rivers to floodplains, mangroves and saltmarsh and swamp forests and many more. We define it in a way that is not too restrictive because we want to acknowledge how interconnected all the systems in a water catchment can be.

“If you are looking to protect a saltmarsh for example, you have to look beyond the borders of the saltmarsh and look at the river and so on.”

The NCC is focused on coastal wetlands due to their role in: climate mitigation – by sequestering carbon from the atmosphere; and in climate adaptation – reducing climate impacts including erosion and lessening impacts from storms on coastal communities.

“Coastal wetlands have cultural significance for Traditional Owners. They have value for local economies in the form of tourism and recreation. They purify water and, for lots of our primary industries as well, they effectively power them – such as our oyster industry and fisheries.

“Without healthy coastal wetlands those industries would really struggle.”

In addition to the coastal wetlands that have been destroyed, “plenty” have been degraded, according to NCC’s Sam Johnson.

“We have seen, in many cases, what hasn’t been cleared, what remains, has been degraded in some way. We have seen wetlands with Ph readings like lemon juice. We have seen coastal lakes poisoned with dozens of pesticides so lots of what is still there is struggling and is degraded.”

What are the greatest threats to wetlands?

Acid sulphate soil

The impact of Acid Sulphate Soils is a particular problem in the Northern Rivers region of NSW.

NCC visited the Tuckean Swamp, part of the Richmond River catchment, the river that flows past Ballina.

“The site we visited has previously been tested to have water as acidic as lemon juice.

“As recently as two years ago there had been mass fish kills along that river, a coastal river.

“I think a lot of people think [fish kills] are confined to inland rivers but we get mass fish kills along the coast,” Johnson said.

Acid sulphate soil causes problems when wetlands have been previously drained, mostly for agriculture.

“The soil there naturally harbours acid sulphate so once that reaches the air, after the wetland has been drained, it oxidises and when that flows back into the river it acidifies the waterways and that causes lots of damage.”

Pesticides

Pollution runoff presents problems for the health of coastal wetlands, particularly pesticides.

Johnson recalled his visit to Hearnes Lake near Woolgoolga (north of Coffs Harbour) where over a dozen pesticides were found in the water.

“That was tested by a community member, not the government, and she found pesticides there that are banned in many countries and, actually, a pesticide that’s banned in Australia. That has led to that Intermittent Closed and Opened Lake or Lagoon (ICOLL) there at Hearnes Lake being described as near dead just from that pesticide alone.”

Over-development

Inappropriate developments in wetland catchments cause runoff from the clearing of vegetation that has a direct impact on the health of the wetland.

“It is an interesting thing with the development, compared to other ecosystems and development, the boundaries of lots of weltands themselves are relatively well protected,” Johnson explained.

“It is those things around the wetlands and within the catchment, for example, run off into the wetland from the catchment, that is where lots of the impact from development comes from.

“It is not necessarily a wetland being built on top of; often it is a wetland being surrounded by development and run off and the impacts that come from that which is the main issue we see in that regard.

“There certainly are developers out there that do want to develop on flood plains. I have encountered it in Western Sydney. There were a couple of developers pushing for loosened restrictions for building on floodplains. That would have certainly presented a threat for the catchment.

“What doesn’t happen in the planning system now is a recognition that these systems are interconnected and if you don’t have a healthy river that is feeding into the wetland then the wetland itself won’t be healthy.

“Inappropriate developments are an issue for the environment in general and the planning system needs to be able to solve the housing crisis on the one hand but certainly not do that at not only the expense of the environment but also the expense of people.

“If you are to remove coastal wetlands you are putting coastal communities at greater risk and if you are building on floodplains you are putting communities at greater risk as well. So it is not just a matter of the health of the wetlands but also keeping them in tact is crucial for the houses that already exist and the houses that go up in appropriate areas.”

Climate crisis

The interplay between the climate crisis and coastal wetlands cannot be understated, according to NCC.

“Coastal wetlands sequester more carbon than any other ecosystem naturally and they do so at a rate significantly quicker as well,” Johnson told The Point. “For example, you are looking at many more magnitudes carbon sequestration from the atmosphere than lots of terrestrial ecosystems such as forests; and they are effectively the world’s predominant carbon sink in terms of the land mass that they occupy, the amount of carbon they are taking in from the air is disproportionately high so they are really important in that regard.”

While sea level rise may benefit some wetland systems – mangroves can do what is called accretion which means they build themselves up. For others, saltmarsh in particular, the consequences of sea level rise are expected to be dire.

Blue carbon

The term ‘Blue Carbon Ecosystems’ refers to coastal wetlands and marine ecosystems that are extremely effective at sequestering carbon from the atmosphere and storing it.

The Federal DCCEEW has been funding blue carbon projects in Australia and other countries since 2021.

“There’s an incoming opportunity for lots of funding to be put into these blue carbon projects through carbon credits and so on,” Johnson said.

“This market is coming in and I think NSW should be prepared in that people should be able to take advantage of this and earn money from their land.

“An example would be a coastal farmer whose land has now become unviable due to sea level rise. A way to continue earning from that land, and a way to provide a different type of public good as their land becomes unviable for agriculture, could be restoring coastal wetlands on the property, sequestering carbon and earning some money through the blue carbon market.”

NSW lags behind

The NSW Government does have a Blue Carbon Strategy . However, according to the NCC, the NSW planning system is lagging other states in its preparedness to take advantage of the emerging market in blue carbon.

“NSW is unfortunately behind the pack when it comes to this. If you are to put in a request for a restoration project for a wetland at the moment in NSW, you have to go through the same planning pathway as a developer who wants to build a block of flats or any for-profit development and that is really prohibitive for small community groups and NGOs.

“We are really missing out on opportunity here because the money is going to start flowing in and we just don’t have the legislative framework in NSW at the moment for these developments to make any sense.

“It is really expensive. It is really time consuming. Even if you own the land and you are ready to restore it to wetlands the loopholes that you have to get through and the amount of bureaucracy that you have to get through is quite astonishing, there are dozens of pieces of legislation that would apply to it.

“The government knows that it is a problem and it needs to be fixed.

“It seems it is just not a priority for them which I think is a bit of a mistake.

“In the age of a climate crisis you really want to be protecting people from the impacts of climate change and that can’t be done if it is prohibitively difficult to restore a wetland but also there is money that is going to be coming in and it is going to be flowing in to the other states where the investment is easier to apply to a coastal wetland restoration project.

“We really want to see the government prioritise this so that wetland restoration and nature restoration in general has its own fit for purpose pathway through the planning system so that people doing it don’t have to go through the same pathway as a for-profit developer.

“Multiple parties have met with the state government about this, they are very much aware of the issue. We haven’t seen any movement yet so we are going to keep pushing on that.”

Taking action in 2025

According to Sam Johnson, many community and grass roots groups are working hard to protect and restore NSW coastal wetlands even while the NSW Government appears to have other priorities.

“In the Northern Rivers we met with Ozfish who are doing lots of amazing work protecting and conserving saltmarsh in the Richmond catchment.

“We met with Positive Change for Marine Life as well who do something similar on the Brunswick River so they are doing physical on grounds work to conserve and restore wetlands but there are plenty of people involved in the advocacy space as well.

“When we went to the Tuckean Swamp we met with Tom who runs a group called Revive the Northern Rivers that is from the advocacy angle trying to raise awareness on these issues.

“I do think there is a lot more than can be done in terms of making people realise not just how important they are for nature but also how important they are for coastal communities. If you were to get rid of lots of these coastal wetlands you’re putting coastal communities at significant risk from floods and erosion and storms. Your water is going to be of lower quality. You are going to get more of those fish kills.

“So I think it is about linking the benefits that coastal wetlands provide to people and making sure people recognise the value they have.

“We are trying to build a movement throughout the state for people who are thinking exactly the same thing that we are, that this needs to happen at scale throughout the state.

“The good thing is systems can bounce back really well, perhaps better than other ecosystems, so restoration is a really effective strategy for wetlands. Of course, it is better to keep them there in the first place and keep them healthy.

“In our trip to the Northern Rivers we went to Urunga and visited the Urunga wetlands which is an incredible site that used to be the site in NSW with the most intense toxic heavy metal pollution so it took the number one spot for that and that has now been restored to a healthy functioning ecosystem so my belief is if it can be done there, it can be done anywhere.”

NCC plans to keep its coastal wetland campaign going in 2025.

“The big move for us in the next year is facilitating a broad state network of people that are working on coastal wetlands to restore and protect them. There are a lot of people doing great work but in many cases they don’t know what the group next to them is doing.

“There is not a great deal of communication between groups and we think there is a real space that we can fill to facilitate bringing that movement together and presenting a united front.

“It is not just people who are restoring wetlands but all the stakeholders. Traditional Owners have a very strong connection to coastal wetlands and country, both land and sea. There is the primary industry, the oyster growers.

“Commercial fisheries, coastal wetlands support the fish habitats, they are fish nurseries, so they very much rely on coastal wetlands.

“It is bringing all of these people together so we can present a unified message that prompts the government to treat this seriously, to treat this as a priority so we can get reform that makes restoration possible as quickly as possible.

“There’s bipartisan agreement that this is valuable, unlike lots of other environmental issues, there’s not a lot of pushback on reforming the planning system so that there is a fit for purpose pathway for restoration projects to go through.

“For example the National Party [has been] saying there is too much red tape for farmers who want to restore river bank vegetation so it is not a politically fraught issue which means it could be an easy win for whoever is making that decision.”