A review of the troubled NSW Biodiversity Conservation Act of 2016 challenges the NSW Minns Government to make NSW a Nature Positive state that would give biodiversity primacy over other considerations.

By Jacquelene Pearson

In the foreward to the final report from the Independent Review of the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016, Dr Ken Henry AC, Lead Independent Reviewer, set the tone by stating that, although the Act was only five years old “we cannot pretend that it is ever likely to achieve its objectives”.

“Biodiversity is not being conserved at a bioregional or state scale,” Dr Henry said. “The diversity and quality of ecosystems is not being maintained, nor is their capacity to adapt to change and provide for the needs of future generations.”

Put simply, the BCA, in its current form, is failing nature and the citizens of NSW.

The Review Panel wants the Act to be strengthened to “align with and contribute to national and global frameworks … particularly the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework.”

Henry said the objects of the Act are already obsolete and the principles upon which those objects were based are no longer fit for purpose.

“Global ambition has moved beyond biodiversity conservation to a ‘nature positive’ framing that emphasises the need to repair past damage and to take urgent action to halt and reverse biodiversity loss, putting nature on a path to recovery, so that thriving ecosystems can support future generations.”

Now that sounds like a plan, but how is NSW ever going to get there when the Minns Government is announcing the need to extend the life of coal fired power stations, keeps approving new coal mines and recommenced logging native forests?

According to Dr Henry, the natural environment “is now so damaged that we must commit to ‘nature positive’ if we are to have any confidence that future generations will have the opportunity to be as well off as we are”.

This approach will require “a major reset in public policy thinking” but, according to the review “our future depends on it”.

“The fact of humanity’s dependence upon the quality of the biosphere, in both social and economic dimensions, is as immutable as the laws of physics. The case for giving primacy to environmental repair is inescapable,” he said.

The review made clear that this new approach would give “primacy to biodiversity considerations in a manner not previously contemplated”.

“Just as NSW has led the country in setting an ambitious plan to reach net zero emissions, the state should now commit to a goal of equivalent ambition for biodiversity,” the final report said.

“Without a radical reframing of public policy, humanity faces a future of both environmental degradation and declining living standards,” it said.

Not fit for purpose

According to the Review Panel, the BCA is not meeting its primary purpose of maintaining a healthy, productive and resilient environment and is never likely to do so.

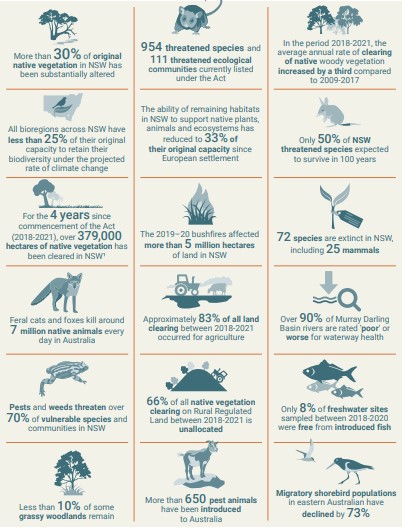

Environmental disturbances continue to put biodiversity at risk across NSW, according to the report. At the top of the list of those risks is clearing of native vegetation, intensifying land use, population growth, infrastructure development.

All of which are causing destruction, alteration and fragmentation of habitat. Weeds, feral animals, water extraction and native forest logging are exacerbating damage to ecosystems and habitat. And then, of course, there is climate change.

The final report of the BCA Review made it clear that the Act’s failure to achieve its principal purposes has serious implications and is “contributing to the continuing deterioration of the environment. This impacts the wellbeing of all citizens of NSW, particularly Aboriginal communities for whom the loss of biodiversity presents as a loss of cultural integrity.”

One of the major problems with the BCA uncovered by the review is its lack of primacy and the fact it is undermined by other Acts including Local Land Services, planning legislation and public and private native forestry.

The review stated its effectiveness is limited but also that there has been limited data collected about its effectiveness.

“Key programs are limited in scope, under-resourced and lack sufficient monitoring, reporting and evaluation. Key advisory resources such as the Biodiversity Conservation Advisory Panel are underutilised,” it said.

The involvement of Aboriginal people is not well developed. The Act’s regulatory provisions are complex, uncertain and expensive. The offset scheme hasn’t produced the supply of credits needed to meet demand.

Biodiversity considerations are not addressed early enough in NSW development assessment and approval processes due to the lack of primacy of the BCA.

Stakeholders lack access to transparent data to inform decisions about biodiversity impacts.

Primacy and integrity

The review makes 58 recommendations under eight headings: a new nature positive architecture for NSW; Nature Positive Strategy; Nature Positive Spatial Tools; Nature Positive Development; Species and Ecosystem Recovery; Leveraging Private Investment; and Intersections with other Acts.

In a nutshell, the review has called for the BCA to have primacy over competing pieces of legislation. It wants to see Aboriginal people fully involved in the design and implementation of policy and programs for conservation and restoration of biodiversity.

It wants the Act to be able to proactively address climate change impacts on biodiversity and believes the Act should ‘guide and promote’ investment in conservation and restoration.

“Those affected by the regulatory provisions of the Act should have much greater certainty, face less complexity and experience lower compliance costs including through the development of a single spatial tool to clarify regulatory expectations.”

More needs to be done, according to the review, to expand the supply of offset credits by assisting landholders to enter Stewardship Agreements and giving greater credit value to restoring sites and protecting connected sites.

The review also wants to see the focus of the Act shifted from threatened species to strategic planning and management of biodiversity to achieve nature positive outcomes.

It wants to see more done to promote and support private land conservation through the Biodiversity Conservation Trust.

“Stronger protections are needed to protect land under a conservation agreement from incompatible land use such as mining exploration,” it said.

Single Spatial Tool

This is to be developed by the Minister for the Environment and will identify ‘no go zones’ or areas that cannot be cleared, developed, or traded off using offsets.

According to the review, identification of no go zones should be based on the scientific criteria currently used to declare Areas of Outstanding Biodiversity Value – World Heritage Areas, Ramsar wetlands, habitat corridors and climate refugia.

According to the review, this spatial tool should be developed and maintained by tapping into traditional Aboriginal knowledge and through community consultation on areas proposed for mapping.

It will be used to identify areas of high biodiversity value, priority areas for restoration, connectivity and climate adaptation that should be prioritised for investment.

“It should draw on high quality data to support the design of policy and on-ground delivery programs.”

One of its main advantages would be to “promote landscape connectivity and ecosystem resilience”.

“Identifying and providing robust information on biodiversity in a single spatial tool will enable upfront consideration of biodiversity, provide certainty and ensure consistent and strategic decisions, supporting nature positive outcomes,” the report said.

Although promised in 2016, the review heard that a Native Vegetation Regulatory map, “has not, for the most part, yet been published”. The review argued that a single spatial tool would support better decision making.

Whole of government

Resources set up under the Act have been under-utilised, according to the review, including the Biodiversity Conservation Investment Strategy and the Biodiversity Conservation Advisory Panel. Both have opportunities to contribute to a new Nature Positive architecture, according to the review.

The review report was emphatic that unless planning and land use laws recognise the primacy of the BCA and fall under a Nature Positive paradigm, any changes made to the BCA, principles and implementation, will flop.

“The new architecture will not be successful without better integration and consistency of legislation affecting land use across the state, and outcomes rigorously assessed and publicly reported.”

What next?

The NSW Government will now consider the BCA review in tandem with the review of the native vegetation provisions of the Local Land Services Act 2013, in consultation with key stakeholders, while developing a whole of government response.